Marge Engelman at 98: Looking back on a lifetime of learning, serving and breaking barriers

Born in rural Illinois in 1927, Marge Engelman’s parents had a traditional path planned for her: marriage, children and a life dedicated to family. But Engelman had other plans.

At age 98, she reflected on the life she built that did include family, but also four degrees, a pioneering career in higher education, artistic accomplishments and service to learning communities often overlooked.

“I was supposed to get married and have kids, but I was restless,” Engelman said. Also smart, curious and driven, she took a road less traveled by women of her day to become one of the first female administrators at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay. After a commendable career, she continued to take courses through UW–Madison Continuing Studies as a senior auditor well into her 70s.

In fact, Engelman charted a course for nontraditional learning throughout Wisconsin. What can we learn from the incredible life of this quintessential lifelong learner?

Defying expectations from day one

Welcomed into Engelman’s home, you’re greeted with a sense of vibrancy, play and joy. An accomplished fiber artist, she fills every surface—walls, shelves, and tables—with her colorful work. Using whimsically fashioned textiles, thread and found objects, her art often focuses on children’s nursery rhymes but also includes pieces with political messages.

Marge holds one of her children’s books, with illustrations from her artwork. Photo: Buri Lor

“I think creativity keeps people healthier, happier and alert for a long time,” she said, having recently shared her art with her retirement community in a “creativity in aging” display.

Don’t let her work with soft materials, quiet voice and calm demeanor fool you. She’s fought hard for her path to a creative life full of learning.

In the 1930s, her parents moved their family so she and her brother could attend a better school, a decision that paid off. Engelman graduated as valedictorian and, despite her parents’ reservations about college, a high school counselor encouraged her to apply. With the help of a grant, she attended Illinois Wesleyan University, where she met her future husband, Ken. She graduated in 1949 with a sociology degree.

While Ken was in seminary at Northwestern University for four years, Engelman acquired a master’s in education at Northwestern and had two children after graduation. She continued to pick up credentials, courses and degrees as she followed Ken, a Methodist minister, across the state – for example, commuting for two years to get a master’s in related art at UW–Madison.

After moving to Green Bay and securing a job, Engelman again commuted to Madison to earn her Ph.D. in continuing and vocational education in 1977. As she advanced her own education, she gained a deeper understanding of the struggles women faced in pursuing degrees and careers.

“I did an interdisciplinary doctorate (at UW–Madison) on creativity in aging women,” she said. “I worked with a group of women in Green Bay who were over 65 and pressed them to do creative things. Many of these women told me early on they couldn’t do it, but with some encouragement, they began to see the possibilities.”

Engelman started seeing possibilities in her own academic and professional career, recognizing the potential to make education more inclusive.

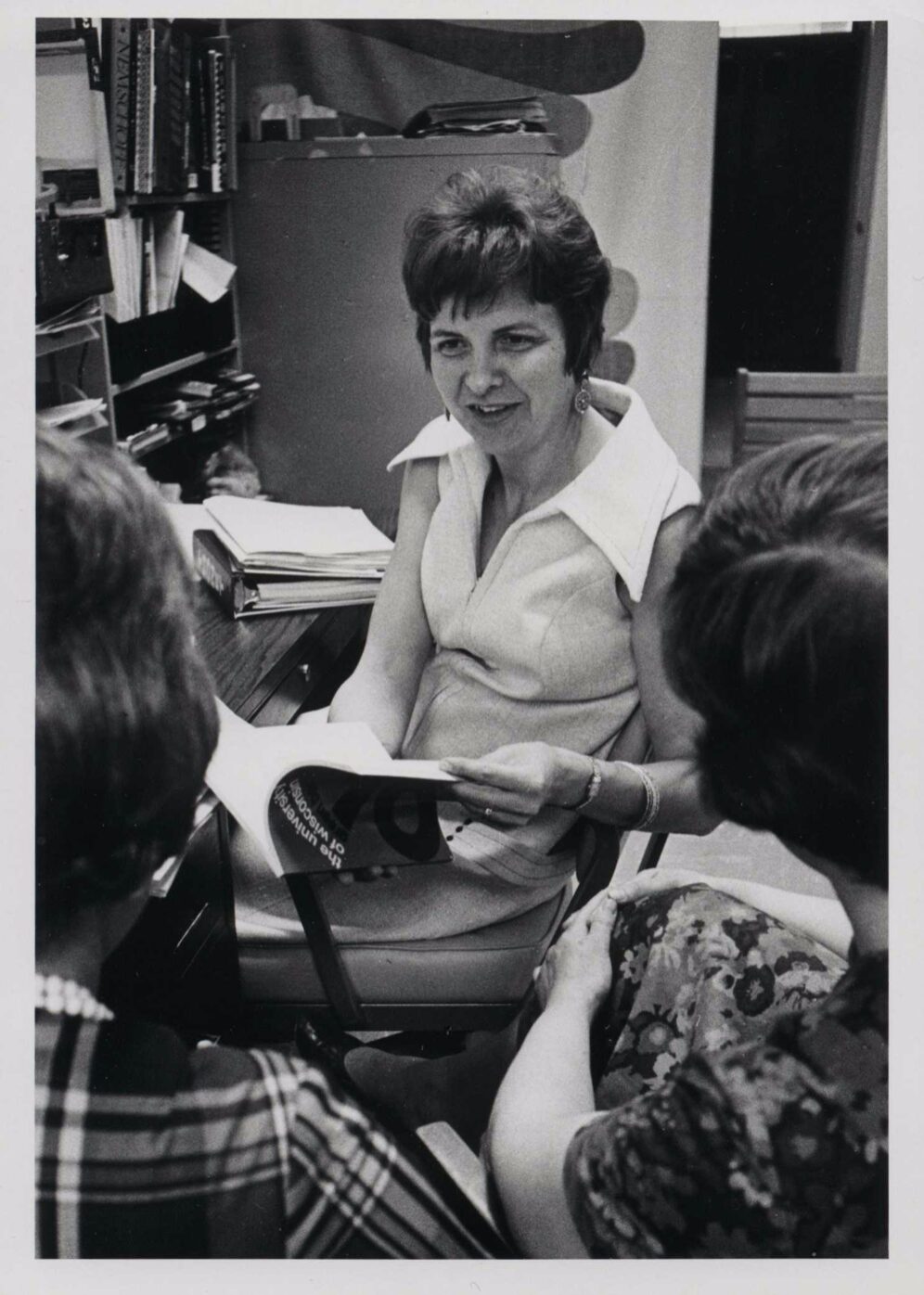

Marge talks with peers at the University of Wisconsin- Green Bay. Courtesy of UW-Green Bay Archives.

Blazing a trail at Green Bay

Engelman’s career in higher ed began in 1965 at UW-Fox Valley (which closed in 2025) where she taught courses in design. Hired at UW-Green Bay before it became a four-year institution, Engelman was on the scene in 1969 when the campus opened.

An assistant to the assistant chancellor, she started at two days a week and was assigned projects such as interior design for the first three buildings on campus: “Think purple shag carpet and burnt orange upholstery,” she added with a giggle.

Eventually, she was charged with community outreach, focusing on returning adults. In 1972, Engleman was appointed director of adult education – the first position of its kind across the state system – and later director of outreach.

She became such an expert on nontraditional students that administrators from UW–Madison consulted with Engelman on their continuing education program.

“Many people in the Green Bay area didn’t have a degree and wanted one. I spent hour after hour talking to returning adult students, and they had fascinating stories,” she said, sharing the example of Gisela Moyer. In the 1960s, Moyer moved to the U.S. from eastern Europe with her GI husband who was stationed near her small town. They had four children, and Moyer – like Engelman – wanted more.

“She was scared to death about going to school. I remember taking her by the hand and walking her through the process,” Engelman said. “Once she got started, she took off, got her fine arts degree from Green Bay and became a professional artist.”

Paving the way for others

It wasn’t easy being one of a small number of female administrators in higher ed. At one point, Engelman documented disparaging remarks from colleagues – mostly men.

“One administrator told me, ‘Well, I can only see you as a sex object, not an administrator,’ and a dean told me, ‘I just don’t know how to treat you. I’ll just treat you like I treat my wife,’” she said. “At that time, women weren’t supposed to cry. I’d go to the bathroom and cry to get it out of my system then go back to work.”

Despite discrimination and barriers at every turn, she worked tirelessly.

Her outreach to nontraditional students found learners on tribal lands, in prisons and reformatories, at local malls and even at the Manitowoc nuclear power plant – “We went everywhere to provide education,” she said.

She also invited new audiences to campus. When she suggested they fill empty seats in classrooms with seniors who wanted to audit courses, it was unheard of – and denied. She persisted, the chancellor changed his mind, and seniors poured in, eager to learn. Another chancellor heard about her efforts, took the program to the UW board of regents, and they approved a system-wide senior guest auditor policy.

Recognized for her work removing obstacles to education, Engelman was appointed director of affirmative action at Green Bay — a role she considers her most challenging. In addition to dealing with discrimination and sexual harassment on campus, she brought in speakers, talked to the community about equal pay for equal work and received plenty of criticism for her social justice stances.

One of her proudest accomplishments includes working with other women to start a cooperative childcare center on campus.

“We knew that women with children really needed this resource. I remember there was actually a faculty person, a woman, staunchly against this. I finally told her, ‘You get off my back. We’re going to have this childcare center, and I don’t care what you think,’” she said, in her soft spoken voice. The center allowed countless women to return to school.

Bursting with creativity – and bras

Engelman left UW-Green Bay in 1985 and retired in 1989 after working several years in Extension. But before she left campus, she left a mark not only as a feminist leader but as an artist.

“I got this crazy idea,” she said. “There were things that were said to me and opportunities I didn’t have because I was a woman. I thought people should start talking about that.”

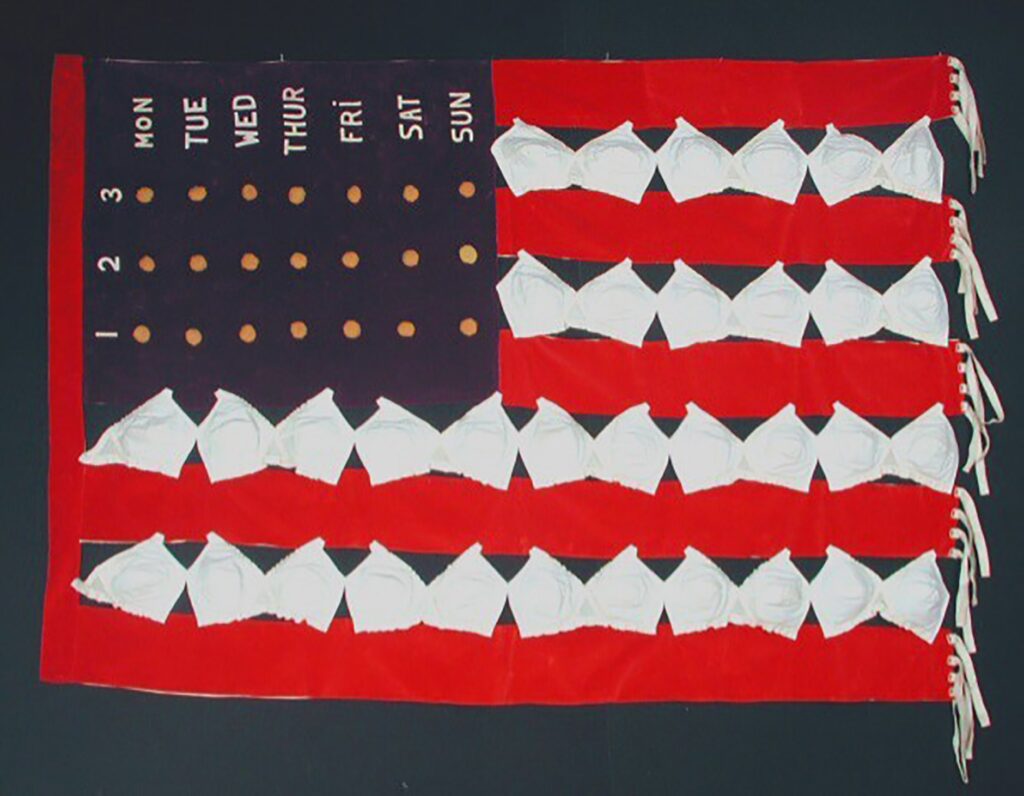

The Land of the Freed-Up Woman, 1971, Marjorie Engelman. Wisconsin Historical Museum, Object #2000.79.1

She got people talking with her 1971 piece entitled ‘The Land of the Freed-up Woman’. Modeled after the American flag, the piece features stripes made of red velveteen and 20 white padded bras. She used foam for the blue and white stars in the corner, meant to imitate birth control pills, which had recently been approved by the FDA. Engelman cut straps from the bras and attached them to the banner’s edge to create a fringe.

After hanging in the UW-Green Bay art gallery, she put it up in her office, until the chancellor told her to take it down. The work was featured in an exhibition in the Neville Public Museum in Green Bay, on Wisconsin Life and at a National Organization for Women meeting. It’s now treasured by the Wisconsin Historical Society.

After retiring, Engelman continued down the artistic path, providing art workshops at senior centers and writing numerous books for adults and children – including seven publications focusing on “aerobics of the mind.”

“A teacher in 3rd grade told me I had no artistic ability,” Engelman said. “I couldn’t color inside the lines.” That didn’t stop her from getting an art degree, teaching others to be creative and continuing to create herself.

Learning never ends

These days, you might find Engelman in a book discussion or working at her dedicated art table on her latest fiber creation. At 98, she’s sharp, engaged and still learning.

The quintessential lifelong learner, Marge sits at her computer in her Madison home. Photo: Buri Lor

In fact, until 2003 she was taking courses at UW–Madison. Between 1991 and 2003, when Engelman was 64-76 years old, she audited 17 courses as a senior. From environmental studies and psychology to American Indian studies and art, Engelman took her seat in the classroom among undergraduate students decades younger than her to quell her thirst for knowledge.

When asked how she accomplished so much, she humbly shied away from taking much credit. When asked about the secret to living a long and healthy life, she doesn’t hesitate: “Be stubborn,” she said with a warm smile. Persistence brought her through a biased educational system and helped her shepherd others through it, too.

Throughout her career and beyond, Engelman’s been recognized for her contributions. In 2019, she received the Albert Nelson Marquis Lifetime Achievement Award.

She continues to influence women: In March 2002, a Madison high school teacher used Engelman’s bra flag to inspire her women’s history class to make a modern version.The students’ creation consisted of white bras tied to a chicken wire frame that they painted as the American flag. On a glass cover over the front of the piece, the students added text from the failed Equal Rights Amendment.

It brought Engelman to tears. In a brief essay response to the students’ piece, Engelman wrote:

“I cried because their interest and concern is hopeful for the future of both men and women. … I cried because I am moved that the art piece that I did inspired a group of young students to do their own thing. … My feelings are a mixture, but mostly joy and appreciation for a new generation who is seeing the light of what a world of true equal rights for women could be like.”

Thanks to the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay for background information on Marge Engelman, including this oral history interview. Read more history of continuing education at UW–Madison at our history blog.

Article was written by Lisa Bauer.